EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the first of a 3-part series on the 1974-75 NBA Champion Golden State Warriors.

Part Two chronicles the Western Conference Finals against the Chicago Bulls.

Part Three tells the story the NBA Finals sweep of the heavily favored Washington Bullets.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This series would not have been possible to write without the microfilm department of the San Francisco State Library. If you live near a university, go to their library and look at old newspapers on microfilm. You will be amazed what you learn.

Oh, and the internet helped, too, especially Basketball-Reference.com and Wikipedia. Thank you.

The 1975 Golden State Warriors were arguably the most improbable NBA champions of all time.

They had one proven star, Rick Barry, and eleven other guys. That may sound harsh, but it’s true. The 1973-’74 Warriors had been pretty good, finishing second to L.A. in the Pacific Division (you didn’t have to say L.A. Lakers back then, you just said L.A.). Only four teams from each conference went to the playoffs, though, and the Warriors’ 44 wins were fifth best in the West.

Rather than build on that success, general manager Dick Vertlieb did some re-structuring, and entered the season having lost four key players. Center Nate Thurmond went in a trade to Chicago; forward Cazzie Russell signed with L.A. as a free agent; New Orleans selected guard Jim Barnett in the expansion draft; and forward Clyde Lee was lost in a trade too bizarre to explain here.

40 years later, Thurmond is the only one of those names who would be recognizable to most basketball fans, but Russell scored 20 points per game in 1974, Barnett chipped in 11 off the bench, and Lee, a one-time All-Star, averaged over 11 rebounds per game. Combining the four of them, the Warriors lost 50 points and over 30 rebounds per game. (Note – Jim Barnett’s NBA story is one worth knowing more about. Dan Brown of the San Jose Mercury News chronicles it here)

Replacing those players were some little-known arrivals and some entirely unknown men. Center Clifford Ray was obtained in the Thurmond trade with Chicago, along with a pick and some cash. It was hard for Warriors fans to get excited about that deal. Dick Motta, then the coach of the Bulls (he won an NBA title later in his career with the Washington Bullets), felt he needed a better center, and he took the man who was the very first draft pick of the San Francisco Warriors eleven years before. It hurt badly.

The Warriors’ draft was also confusing. Their first-round pick, No. 11 overall, was 6-4 forward Keith Wilkes, out of the basketball machine down at UCLA. The Warriors hadn’t hit with a first-round pick since Lee back in 1966, and Wilkes seemed way too slight to ever play forward in the NBA.

In the second round, Golden State saved on some travel costs by picking guard Phil Smith out of the University of San Francisco. Smith was a more popular selection than Wilkes, obviously, but the West Coast Athletic Conference (San Francisco’s conference back then, now called the West Coast Conference) has never been a league that turns out All-Stars.

The team did have some veterans left from the previous year, though. This deepens our portrait of a champion, the only champion in the history of the Golden State Warriors.

*

First, there was Rick Barry, then at the apex of a great career. A difficult man to get along with on and off the court, Barry had been a basketball gypsy (I didn’t make that up — his autobiography published in 1972 was called “Confessions of a Basketball Gypsy.”)

That’s right. Six years into his pro basketball career, Rick Barry wrote his life story. He was 28.

The “Gypsy” part refers to the fact that he was drafted by the Warriors, had two great years, led the NBA in scoring, and led the Warriors to the NBA Finals, where they lost to former Warrior Wilt Chamberlain and the 76ers in 1967. He then jumped to the Oakland Oaks of the ABA, which was not only paying him $500,000 over three years but also hired Barry’s father-in-law, Bruce Hale, as the coach. Barry had to sit out a year due to the reserve clause in his contract with the Warriors. This is basically the same reserve clause that Curt Flood took all the way to the Supreme Court two years later, basically clearing the way for free agency in all sports.

When Barry finally got to play for Oakland, he was fantastic, and was leading the league in scoring when he suffered a knee injury in December. The following year Oaks owner Pat Boone sold the team, and they moved to Washington, D.C.

After one year in D.C., the team moved to Norfolk, Virginia, and became the Virginia Squires. Barry, who was already upset about the move to Washington, drew the line at playing in Virginia. He was quoted in Sports Illustrated as saying he didn’t want his kids growing up with Southern accents. The Squires gave him his wish, trading him to the New York Nets.

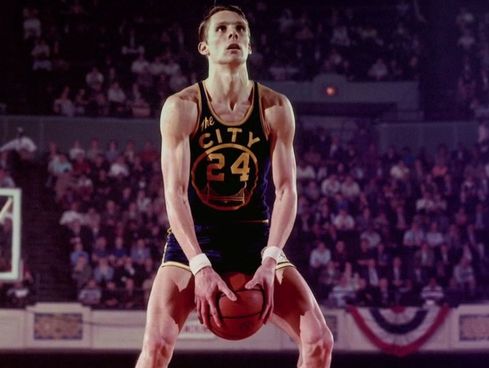

He played two years with the Nets, including one trip to the ABA Finals. In 1972, a U.S. District Court judge ruled that Barry would have to return to the Warriors after his contract with the Nets was up, which it was after that season. He came back to his familiar No. 24, which owner Franklin Mueli had set aside, always believing he would return.

Barry’s knees were bothering him more consistently at this point in his career, and while he was still putting up good numbers, his game was changing. At 6-7, he had been a low post player, but he moved his game farther away from the basket. Always one of the best passing big men in the game, Barry is credited with pioneering the “point forward” position, and he kept defenses honest with an excellent outside shot.

He was THE MAN.

In his first season back, 1972-’73, the Warriors upset No. 1 seed Milwaukee (yes, with Kareem and Oscar) in six games, but were smoked by Wilt Chamberlain and Jerry West of the Lakers in the West finals. Barry averaged only 16 points in the Bucks series, but he led six players in double figures. As I mentioned before, they won 44 games in the 1973-’74 season, but missed the playoffs.

*

Now that you have the background on Barry, let’s finish getting to know the 1975 Warriors.

Another veteran who returned for the Warriors was Jeff Mullins. He was a shooting guard who had been to three All-Star games while Barry was doing his ABA thing. He had been drafted by the St. Louis Hawks in 1964, taken by the Bulls in the expansion draft in 1966, and then, before he ever played for Chicago, he was traded to the Warriors for aging superstar point guard Guy Rogers.

Mullins had starred at Duke, but I think it’s fair to say that neither the Warriors nor the Bulls knew how good he would be in the NBA. In 1974, however, he was two years older than Barry and four years older than anyone else on the team. Like David Lee in 2015, he suffered an injury in training camp, and by the time he was ready to play, the team was 10-3 and Charles Johnson was firmly ensconced in the starting lineup. Also like Lee, Mullins embraced his role coming off the bench, and he was a crucial part of the team.

Starting along with Johnson in the backcourt was veteran Butch Beard. He had come to the Warriors the previous year after one-season stints in Atlanta, Cleveland and Seattle. He had started in Cleveland, which was an expansion team, and he made the All-Star team. That actually worked against him, because the Seattle Supersonics traded beloved superstar Lenny Wilkens for him the next year. Sonics fans hated the trade, and Beard had a miserable season in Seattle. The Warriors acquired him in a trade for Mahdi Abdul-Rahman, the former Walt Hazzard, who had been a disappointment in Golden State. Beard was a reserve for the Warriors in 1973-’74.

There were several unproven young players on the 1974 squad that would get the opportunity to be bigger contributors the next year, but none of them were striking fear in the hearts of opponents.

Charles Johnson was a 6-0 shooting guard drafted in the sixth round in 1971 out of Cal (are you getting the picture about the team’s scouting budget?). He didn’t make the team that year, but started getting some playing time in 1972. He was a shooter, a guy whose career would have had a completely different arc if the 3-point line had come into play about ten years earlier than it did.

The Warriors had another small guard named Charles — this one had the last name of Dudley. Nobody ever called him that, though. He was into martial arts, and his nickname was Grasshopper, or more commonly, Hopper. The nickname fit his style of play perfectly, as he was an energy guy, someone who could shut down an opposing scorer for short stretches of time. Like Charles Johnson, Dudley had a difficult path to that ’74-75 team. He was drafted by the Warriors in the fifth round in 1972, and waived in camp. In February of that year, he signed with Seattle, but the Sonics cut him after the season. After sitting out an entire year, the Warriors brought him into camp in 1974, and he made the team.

Another second-year player on this team was power forward (that’s what they used to call the “4”) Derrick Dickey. He was a second-round pick out of Cincinnati who had played about 14 minutes per game as a rookie.

The last key contributor to the 1975 Warrior championship didn’t arrive until March. Bill Bridges had been playing in the NBA since he was drafted by the Chicago Packers in 1961. (The Packers played only one season under that name and soon became the Baltimore Bullets, which then became the Washington Bullets.) Bridges had been released by the Lakers in December and then retired.

Bridges had been an All-Star three times with the St. Louis and Atlanta Hawks, and was a great defender and rebounder. The Warriors’ braintrust — GM Dick Vertlieb and head coach Al Attles — was looking ahead to the playoffs. Vertlieb and Attles saw the Chicago Bulls’ Bob Love as a guy they really didn’t have an answer for. Bridges had played well against Love in the past, and the Warriors thought he might come in handy. That decision alone might have gotten them to the Finals.

*

A few words here about Attles…

He was and is the Ultimate Warrior. He was drafted by the Philadelphia Warriors in 1960, and made the team as a defense-first point guard who earned the nickname “The Destroyer.” On March 2, 1962, Attles was a starting guard in Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game. In fact, that was the best offensive game of Attles’ career: He made all 8 shots he took from the field, plus his lone free throw for a perfect 17 points.

The team moved to San Francisco for the 1962-’63 season, and Attles played 20-30 minutes per game for the next eight years. He never scored much more than ten points per game, but was a great defender, and when he took a foul, that shot was not going in the basket.

During the 1969-’70 season, Attles’ ninth with the Warriors, owner Franklin Meuli fired coach George Lee and named Attles player-coach. He held that title for the rest of that season and all of the next, before retiring as a player. For the next seven seasons, the Warriors finished over .500, with a high-water mark of 59 wins in 1975-’76. After that season, Vertlieb retired as GM, and Attles took over that job as well. He stepped down from coaching after the 1982-’83 season, having won a little more than half of his 1,075 games. He resigned as general manager after the 1997 season, but he never left the club, serving as an advisor, an ambassador, and a reminder of the One Shining Moment in the team’s history.

In 1974-75, Attles was the perfect coach for this team. Just a few years older than Barry, he was the embodiment of the 1970s, right down to his wide lapels and bell-bottom slacks. He preached ball movement and team play, his star bought in, and everyone else followed along. He and assistant Joe Roberts, who coached the clinching Finals game when Attles was ejected early, were ahead of their time in their approach to the game.

*

Before we conclude this piece — part one of our look back at the 1974-’75 Warriors — two other names bear mentioning, just because they completed the whole idea of that team.

Everybody counted on this team, even rookie Frank Kendrick and third-year pro Steve Bracey, even though they rarely played.

Kendrick was drafted in the third round out of Purdue, and Bracey — drafted by the Hawks in 1972 out of Tulsa — had arrived prior to the season. Kendrick was waived on March 1 to make room for Bridges, but he remains part of the team in the memory of the fans. Neither played again in the NBA.

That’s who the Warriors were in 1974-’75. Next we’ll tell you what they did, and how they stunned the entire sports world. Stay tuned.