It’s something I have written about when covering major-tournament tennis at Bloguin site Attacking The Net. It’s very much worth repeating on a day when Joe Manganiello and I have explored the best NBA Finals series of all time here at Crossover Chronicles:

The length of a sporting event is not the central manifestation or determinant of its quality. (In solo-athlete sports, this is even more true, but it still holds up to a considerable extent in team sports.)

One of the easy — and easily wrong — inclinations of many sports fans in the wake of a close game is to pronounce that game great. Let’s immediately step in and clarify that when one refers to greatness, the implication is that the quality of the event, the level of play, reached a high plane. Perhaps a subset of fans will connect greatness to entertainment value or dramatic tension (or both), but when a viewer leaves an arena or the seat on a couch at home, s/he should generally be assumed to mean that s/he just saw the sport played with distinction… not just in a few late-game moments, but for most of the afternoon or evening.

If a game was mediocre as a whole but featured a riveting conclusion, one would say, “Man, that was a GREAT fourth quarter/overtime/endgame sequence!” A great game is the whole enchilada, with greatness being something more than good — the 2015 Warriors, not the 2015 Wizards or Trail Blazers.

This is the essential nature of greatness, especially as seen through sports commentary and the instinctive reactions we make to various competitions and events: If we assign the label of “greatness” to everything, we lose the distinction between that which is merely “good” or “very good” and — on the other hand — that which is truly elevated and lofty, worthy of inclusion in the pantheon of classic showcases.

It is true that in non-NFL North American team sports — in other words, all the major North American team sports with playoff series — having six games of quality trumps five games of relatively equal quality. For this reason, the length of an event isn’t entirely removed from the discussion of its quality. However, this is not the foremost measurement, and never is. It could be a third or fourth tiebreaker between two relatively equal series, but it’s never the first point of reference.

Along a similar but somewhat disconnected line of thought, it is naturally true as well that a series reaches a higher plateau when both teams play extremely well. This is much the same as saying that a great six-game series is better than a great five-game series. It’s obvious. However, a lopsided series in which one team plays well is better than a close and riveting series in which both teams play — if not poorly — without added measures of artistry, ingenuity or cleverness.

Furthermore, as an addendum to each of the points just raised — the first about the length of a series, the second about single-team brilliance in a short series trumping two-team blandness in a long series — it is important to stress that what’s true for series can also be true for single games.

No NBA Finals series illustrated these distinctions better than the 1994 NBA Finals between the New York Knicks and the Houston Rockets.

*

In the 1990s, the Detroit Pistons and Chicago Bulls started the decade with very impressive Finals performances (particularly in the middle three games on the road) against the Portland Trail Blazers and Los Angeles Lakers. However, as the decade continued, the nature of NBA basketball became more plodding and labored. The 1993 Phoenix Suns and the 1996 Seattle Sonics were fun teams to watch, but for the most part, the 1990s drowned in a sea of stagnant isolation basketball and a rougher style which discouraged free-flowing movement. The classic embodiment of this trend was the 1994 Finals, in which the Knicks — the “Slowtime” successors to Pat Riley’s “Showtime” in L.A. with the Lakers — engaged the Houston Rockets in a series of knock-down, drag-out games.

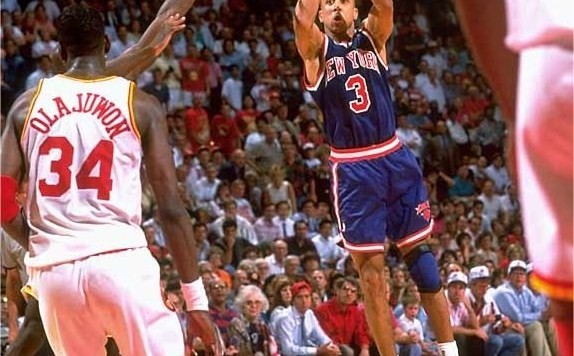

The pace and style of the series were conducive to close games and immensely dramatic denouements. The defining moment of the series was in fact the very end of a game — Hakeem Olajuwon blocking John Starks’s potential championship-winning jumper in the final seconds of Game 6, sending the battle to a Game 7 the Rockets would win.

Was the series interesting as a championship drama between one franchise that hadn’t won a crown in over 20 years, and another which had never lifted the Larry O’Brien Trophy? Sure. Did the series make for great television, drenched in the tension and suspense the medium thrives on? Absolutely. Did both teams earn high marks for hustle and work ethic and determination and all those feel-good intangibles? Of course they did.

Yet, those were side issues when placed next to the central question: Was this top-quality basketball? No. John Starks’s Game 7 performance underscored and affirmed the claim that this series did not showcase basketball at its best. The highest-scoring game of the whole series was Game 3.

Final score: Rockets 93, Knicks 89, for an average of 91 points per team and a total of 182 points scored.

Yes, that was the high point in a series largely played in the 80s.

Sure, it went seven, with the winner not emerging until the very end. Sure, the images of Pat Riley and Patrick Ewing absorbing the disappointment of falling just short of an NBA title made for tremendous television on NBC. The city of Houston witnessing its first major pro sports championship — with Olajuwon, a favorite son, at the heart of the effort — was also a special thing to watch on television. No question.

Yet, the quality of ball suffered in the series, and there’s little if any doubt about that claim.

*

Yes, give me the 1977 Finals between Portland and Philadelphia over the 2014 Finals between San Antonio and Miami. Both series were captured by one team playing team-oriented basketball at its best, but Blazers-Sixers was one game longer than Spurs-Heat. In that example, the length of a series had a role to play in determining the quality of the event.

Yet, when using the 1994 Rockets-Knicks Finals as an example, give me that five-game 2014 Finals with the Spurs and Heat as a better Finals series. Similarly, give me 2012 Thunder-Heat — in which Miami was simply marvelous — over the six-game San Antonio-New Jersey Finals from 2003, or even the seven-game 2005 Finals between the Spurs and Pistons. Game 5 of that 2005 Finals series was a classic, but most of the rest of that series stunk. The short and sweet series with one team being luminous and dazzling — the Sixers’ four-game sweep of the Lakers in 1983; the Pistons’ clinical sweep of the Lakers in 1989 — easily exceeds a seven-game series in which two teams largely fail to be at their best.

Length; closeness; quality. Don’t think they’re all intimately connected to each other. Sports are more complicated than that… especially in the NBA Finals.