Days after the induction of 11 new members into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, we’re wondering here at Crossover Chronicles: “Which other players should be part of the club and get their ticket to Springfield?”

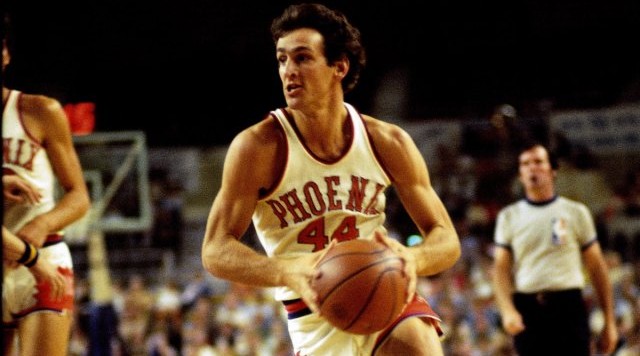

One player who has not yet received his passport to basketball immortality is Paul Westphal, who starred for the Phoenix Suns in the latter half of the 1970s, and later coached the team to the 1993 NBA Finals. Westphal played and coached for the Suns in an NBA Finals series, having worn a uniform for Phoenix in the 1976 Finals against his former team, the Boston Celtics.

*

As always, a great place to start in any Hall of Fame discussion is to compare Player X against another player at the same position(s) who is already in the Hall. One could choose many possible players to put up against Westphal. Let’s go with Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, the marvelous guard for the Baltimore Bullets and New York Knicks.

First off, Monroe’s career was better than Westphal’s, if you absolutely had to make a comparison. Monroe sustained his prime years for a longer period and was a noticeably more prolific offensive player. Give his stats an overview and you’ll see.

Westphal’s career stats aren’t as imposing — you can analyze them here — but his Hall of Fame case is buttressed by a closer look at a few specific categories. Even more to the point, Westphal’s Hall of Fame candidacy is bolstered by an appreciation of the contexts in which he and Monroe played.

*

If you trace the trajectory of Earl Monroe’s career — one which is indisputably worthy of Hall honors — you will notice that in his prime, from the late 1960s into the mid-1970s, he played with great centers. In Baltimore with the Bullets, Monroe was able to partner with a young Wes Unseld. This is why the Bullets were able to make the 1971 NBA Finals against Kareem, Oscar, and the Milwaukee Bucks. When Monroe went to the Knicks during the 1971-1972 season, Willis Reed — like Unseld, a Hall of Fame big man — became a teammate. Monroe definitely forged a legendary career, but let’s appreciate the fact that he had great centers and generally balanced teams to work with, especially in New York.

Clyde Frazier, Bill Bradley, Dave DeBusschere, Jerry Lucas, and Reed — all of them Hall of Famers in their own right — joined Monroe on the early 1970s Knicks. Monroe succeeded handsomely as an individual, but his circumstances contributed to the development of his career.

Westphal, in Phoenix, did not have nearly as much support. Despite helping the Suns to the 1976 Finals and then within one game of the Finals in 1979 (the team led the Seattle SuperSonics, 3-2, in the West Finals, but lost Game 6 at home and Game 7 on the road), not one player from those Phoenix teams from 1976 through 1980 is a member of the Hall of Fame as a player. (Pat Riley, a player on the 1976 team, is of course in the Hall, but as a coach.)

What you also have to realize about the Suns — as mentioned here earlier in the summer — is that the franchise has never had a great center… at least not in his prime (right, Shaq?). What was true in the 1993 NBA Finals against the Bulls (with Mark West) and in the 2005 West Finals against the San Antonio Spurs (with Amar’e Stoudemire, a natural 4, playing the 5 to fit Mike D’Antoni’s seven-second offense) was also true in the late 1970s. Alvan Adams was an undersized center with a power forward’s game. He, like Westphal, merits Hall of Fame consideration. So does the best pure shooting guard in Suns history, Walter Davis. However, compared to Monroe’s Knicks and other great teams from the 1970s, Westphal still had comparatively less to work with. Specifically, he didn’t have an elite true center on the floor at the same time.

Working within those constraints, it needs to be pointed out in Westphal’s statistical profile that he finished with a career shooting percentage above .500 (at .504). To amplify that one stat, keep in mind that the NBA didn’t introduce the three-point shot until the 1979-1980 season. Westphal’s best seasons coincided with a point in the NBA’s history when the lack of the three-point line made it harder for offenses to space the floor. When everyone on the court was trying to get a good two-point shot, Westphal hit a majority of them as a guard, on teams which generally lacked a true center.

Beyond all that, Westphal finished with 4.4 assists per game, compared to Monroe’s 3.9. (Yes, Walt Frazier had something to do with limiting Monroe’s assist totals on the Knicks, but the point remains that Westphal remained a skilled and effective passer throughout his career.) Westphal was also a defensive pest at his height, swiping an average of at least 1.7 steals per game in three straight seasons, from 1975-’76 through 1977-’78.

In many ways, this isn’t so much a comparison of Earl Monroe and Paul Westphal. This examination inspires a question, one you need to wrestle with as you evaluate Basketball Hall of Fame candidates from the NBA in the 1970s:

If you swapped some of the Phoenix Suns’ and New York Knicks’ foremost stars — putting the Knicks on the Suns and vice-versa — would any of the late-1970s stars for the Suns be outside the Hall of Fame’s doors right now? As the follow-up, how many of the early-1970s Knicks stars would be in?

Don’t answer those questions. Think about them.

It’s a not-so-Sunny Hall of Fame situation, that’s for sure.