EDITOR’S NOTE: This is Part 2 of a 3-part series telling the story of the 1974-75 Golden State Warriors.

Part One was an introduction to the improbable dozen men who came together to win an improbable championship.

Part Two is the story of the 1975 Western Conference Finals, when the Warriors beat the Chicago Bulls in seven games. They didn’t win four out of seven, they won FIVE… but more on that later.

Part Three is the incredible story of the 1975 NBA Finals, when the Warriors dispatched the heavily favored Washington Bullets in four games.

*

While the Warriors had the better record, it was by just one game. The Bulls had won three out of the four regular-season meetings, with an average margin of victory of 17 points. The Warriors had managed to win the final game of the series, and that win, although it happened in March, gave Golden State home-court advantage.

There was additional intrigue going into the series because the two teams had been involved in a surprising trade before the season started. The Warriors had shipped long-time All-Star center Nate Thurmond to Chicago for fourth-year center Clifford Ray and a No. 1 pick that the Warriors would later use to draft Joe (Jellybean) Bryant, who never played for the Warriors. He was sold to his hometown 76ers, where he kicked off a pedestrian eight-year NBA career. He is most famous for being Kobe’s dad.

But I digress. Clifford Ray was a third-round pick by the Bulls, and worked his way into the starting lineup, but he was a 6-9 guy with limited offensive skills, and Bulls coach Dick Motta wanted more out of his 5 spot. He thought that his path out of the Western Conference (did I mention yet that the Bulls were in the Western Conference until 1980?) was going to go through Detroit (which had Bob Lanier at center) or Milwaukee (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), and he didn’t see Clifford Ray as the guy who was going to get him there.

Nate Thurmond, on the other hand, was a star. He was the third pick of the draft by the Warriors in 1962, and had played in seven All-Star games. He was 33 years old, and his production was declining, but Motta had a team full of veterans, and he wasn’t worried about the long-term implications. He wanted Nate, and the Warriors were willing, so the deal was done. The trade was one of several changes for the Warriors I wrote about in Part One of this series.

The irony for the Bulls was that Milwaukee didn’t make the playoffs, and Detroit lost to Seattle in the first round, so Lanier and Abdul-Jabbar were not around as the Bulls made their playoff run. Besides, Thurmond had been beaten out by Tom Boerwinkle, a 7-0, 265-pound behemoth of a man who had been a starter earlier in his career, but had struggled with injuries and had been forced to the bench by Ray. (Are you following this?) Boerwinkle had a great passing touch for a big man, and a decent outside shot that he used to keep defenders from sagging into his passing lanes.

One more thing on this center situation. The Warriors’ backup, George Johnson, had been cut by Motta and the Bulls in 1971. This isn’t Michael Jordan getting cut from his high school team or anything; Johnson was drafted in the fifth round from a school called Dillard in New Orleans. He was discovered by the Warriors playing on a semi-pro team in Martinez, about 20 minutes north of Oakland. Still, Motta entered this series with two centers he had benched at one time or another, facing two centers he had either traded or cut. You can’t make this stuff up.

*

The Bulls had been regular visitors in the playoffs since the very first year they showed up as an expansion team. Guard Jerry Sloan (pictured, above) had played in 45 playoff games before this series started. Forward Chet Walker, who had starred with Wilt Chamberlain’s 76er teams prior to coming to Chicago, had 92 playoff games under his belt coming into the West finals.

The Warriors, on the other hand, had only two starters who had played significant playoff minutes: One was Rick Barry, who had played in the Finals for the Warriors, losing to Walker’s 76er team in 1967. The other was Clifford Ray, who had been to the playoffs three times with the Bulls. The other three starters had played in a total of 15 playoff games prior to the 1974-’75 season.

That gives you some idea why, despite the fact that the Warriors had home-court advantage, there wasn’t much optimism around the Bay for the Warriors to win this Series. There was even less thought given to Warrior success nationally, as outside of Barry there was nobody on the team that was a household name anywhere else in the country.

One more thing before we start to talk about the actual games:

The management of the Oakland Coliseum arena was used to the Warriors’ seasons ending in April or early May, so they went ahead and booked some dates later in the month. The second game of this series was to take place on a date that was already booked at the arena, so the Warriors had to trade Game 2 at home for Game 4. That would turn out to be important. It would also not be the last time the Warriors would be displaced during this post-season.

*

When the ball went up for Game 1 in Oakland, the résumés went out the window, and the Warriors surprised the Bulls with a 107-89 victory. The lead was single digits after three quarters, but the Warriors’ depth showed in the fourth, and they put up 35 points on the tiring Bulls. Forward Bob Love had 37 points, but Barry countered with 38, and the Warriors had a relatively easy Game 1 win.

For Game 2, the series shifted to Chicago. The Warriors led for most of the second half, and when Jeff Mullins hit a driving layup with 1:04 left, they led 89-86. That’s when the wheels started to come off for Golden State.

Keith Wilkes, the NBA Rookie of the Year out of UCLA, committed a turnover, and Norm Van Lier scored to cut the lead to one. The Warriors inbounded, and Mullins, a ten-year NBA vet, lost the ball to Jerry Sloan. The Bulls had life. Chet Walker, one of the toughest players to stop in the league, attempted to drive past Barry, but the Warriors’ forward knocked the ball away to Mullins.

22 seconds left, one-point lead, shot clock off. A “W,” right? Red Auerbach would light a cigar.

In one of the most improbable events of a most improbable season, Rick Barry lost track of the game situation. He heard the bench yelling to “move the ball,” and he thought they were saying “shoot the ball.”

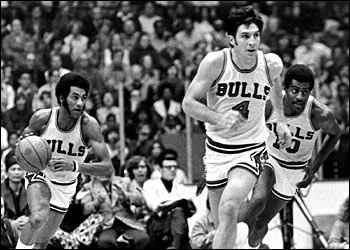

The image above is taken from a Warriors-Bulls game from that series, in Chicago Stadium. Notice in the image: There’s a box on the right-hand side of the picture, next to the baseline official. That’s the 24-second shot clock.

Remember, the 24-second shot clocks were on the floor in those days, on the left corner as you faced the basket. He couldn’t see the shot clock was off, and thought that he had miscalculated. He forced up a shot under heavy pressure, and it didn’t draw iron. The Bulls got the ball and called a immediate time-out. Shaken, the Warriors were not focused when play resumed, and Van Lier hit Boerwinkle under the basket for an open layup with two seconds to go. The Warriors weren’t able to get a shot off, and the game ended with the Bulls winning, 90-89.

The Warriors were devastated. Coach Al Attles opened a side door in the locker room and let the players out before the media came in, so that they wouldn’t have to talk about it. He took the questions from the few media people gathered (The San Francisco Chronicle didn’t send a reporter on the road until the Finals), answered them the best he could, and the team tried to move on.

It’s impossible for me to not mention how much differently a mistake like that would be treated today. A player would never live that down, no matter how the series turned out. In fact, the media and fan reaction would be so powerful that it could change the outcome of the series, just because of the pressure on that player and his team to overcome the error.

Ah, but let’s return to simpler times, shall we? There were a few articles about “Barry’s Boo-Boo” (really, that’s what some writers called it), but for the most part the Warriors were left alone to try to put it behind them. That task got tougher when the Bulls, who felt like they were given new life in the series, hammered the Warriors 108-101 in Game 3, also in Chicago.

The Warriors had gone from having a 2-0 stranglehold on the series to trailing 2-1. Game 4 was back home in Oakland, but that didn’t seem to turn things around, as the Bulls, the lowest scoring team in the NBA, exploded for 37 points in the first quarter and led by 17 points.

Time for a little magic.

In the second quarter, the Warriors’ bench rallied. Jeff Mullins, Bill Bridges and Derrick Dickey provided the offense, and Cliff Ray did everything else. It was a two-point game at the half. In the third quarter, Barry, who scored 26 of his 36 points in the second half, got hot. The Warriors played the Bulls even in the third, and finally caught and passed them in the fourth. Ray played an incredible 45 minutes in that game, with 10 points and 18 rebounds. Bridges, the old man brought out of retirement by GM Dick Vertleib expressly to guard Bob Love if these two teams met in the playoffs, had 7 points and 8 rebounds in 12 minutes. Those contributions were enough to give the Warriors a hard-fought 111-106 victory.

That was escape number one.

Now that the series was tied 2-2, with Game 5 in Oakland, everything was back on track. After all, the Bulls were 2-26 all-time in the playoffs on the road, and the Warriors were almost unbeatable at home. Well, to use an old sportscasters’ axiom, “That’s why they play the game.” The Warriors were outclassed start to finish, and while they lost only by ten points (89-79), reading newspaper accounts makes it seem like it wasn’t really that close.

With their backs against the wall, the Warriors flew to Chicago, knowing that the Bulls’ record at home was as good as their record on the road was bad. The beat writers, Art Spander of the San Francisco Chronicle and Frank Blackman of the San Francisco Examiner, both came very close to writing the team off in their Game 6 previews.

Spander wrote, “Despite the usual words to the contrary, it looks very much like the Warriors will lose. They’ve lost all four times in Chicago this year, twice in regular season, twice in the playoffs, and have won only one game there in the last seven games.”

Blackman wrote, “If the Warriors come out flat in the first period today, it might be advised to switch to the inspirational shows on other stations for solace — because only prayer will get them by in that case.”

Against that backdrop, the Warriors promptly came out flat. Yet, they wouldn’t allow Blackman’s words to become the final story of their season.

They trailed 25-16 as the first quarter came to a close, but Barry hit a long jumper at the buzzer. The Warriors slowly reeled in the Bulls until Keith Wilkes hit a jumper with 4:07 remaining to tie the score at 34. The final four minutes of the half were all Golden State, and when the teams hit the locker rooms for intermission, the score was 46-38. The Bulls got the lead down to five in the fourth quarter, but Barry blocked a shot by Love and hit a jumper at the other end to stem the tide. The Warriors’ star scored 36 points, and had eight rebounds and seven steals, as the Warriors won 86-72 to set up Game 7 in Oakland.

The Warriors had made a subtle change on defense in Game 6, and it might have changed the outcome. Tom Boerwinkle was hurting them with passes from the high post, so Attles decided to have his centers back off the Bulls’ big man. That was a little more difficult to do in those days because zone defense was illegal, so you still needed to be obviously guarding your man, but the Warriors centers sagged into the paint and took away the passing lanes, which had the added benefit of making it more difficult for the other Bulls to drive to the hoop. Boerwinkle, suddenly finding himself open at the free throw line, tried some shots, but stopped after going 1-for-5.

Jerry Sloan later called this game the most memorable of his career.

That was escape Number 2.

Game 7 was a great game. Again, the Warriors came out flat (or tight, or something), and they managed only 16 points in the first 15 minutes of the game. At that point they trailed, 29-16. The Bulls’ biggest lead came a few minutes later, at 45-31, with two minutes to go in the half. The Warriors cut the lead to 11 at halftime, and trimmed five more points off the lead in the third quarter. This is where Al Attles’ use of his bench really paid dividends. Dick Motta played four of his starters 40 minutes or more in this game, at the end of a grueling series.

Barry had a horrible first three quarters of the game, hitting only 2 of his first 15 shots. Attles benched him to start the fourth quarter, going with a lineup of Wilkes, George Johnson, Charles Dudley, Derrick Dickey, and Jeff Mullins. That was the group that stopped Chicago’s offensive flow. Chicago still led 67-61 when Barry came back in the game with about 7 minutes to play. He hit three straight jumpers to tie the game, and while the Bulls surged again, baskets by Wilkes, Barry and Phil Smith gave the Warriors the lead for good at 77-73.

This is a video of the last three minutes of the game. Notice how huge George Johnson was in the final minutes, blocking four shots in the final 2:18. Remember, Johnson was cut by Motta and the Bulls several years before.

The Warriors outscored Chicago 24-14 in the final quarter to win, 83-79. The Improbable Dream Team was on its way to the NBA Finals. The Warriors had won two straight games against one of the toughest teams in the league, and had recovered from losing a game under the worst circumstances imaginable.

Barry, almost the goat several times, between his Game 2 “boo-boo” and his horrible shooting in a few games, hit six of his last eight shots to keep the Bulls at bay. Bob Love, who played all 48 minutes, said after the game, “They wore us down. We ran out of gas.” The Warriors’ bench outscored their Bulls counterparts, 26-3.

Two of those three Chicago bench points came on free throws by Nate Thurmond, who played only eight minutes. It was a frustrating afternoon for the former Warriors All-Star, hearing what used to be his home fans going crazy for his opponents. “I’m unhappy,” Big Nate said, “but I’m happy for Al Attles and Jeff Mullins. Jeff and I used to carry this team over the years, but it seems like we never got the recognition the Warriors get now.”

Boerwinkle, exhausted from playing 40 minutes against much fresher players, said, “We were the better club on paper in this series, and look what happened. The Warriors never quit. They could have folded very easily in the sixth game, but they didn’t. I’ll never bet against them!”

That was escape No. 3.

The Warriors got on a flight the next day to Washington D.C. There would be only two days to get ready for the Washington Bullets, who, after compiling the best record in the NBA (60-22), had beaten the powerful Boston Celtics in the Eastern Conference finals. The Bullets had won three of the four meetings against the Warriors during the season, just as the Bulls had. Everyone expected the Bullets to make short work of the series.

They should have listened to Tom Boerwinkle.

Footnote: Looking back after 40 years gives us an unusual perspective on the reporting of the time. I want to laud San Francisco Examiner columnist Prescott Sullivan for what he wrote about Rick Barry’s mistake that cost the Warriors Game 2. This was written the day that the Warriors would play Game 3:

“Up to this point, Barry’s mistake is without the quality of finality. We mean is isn’t something that can not be remedied. Should the Warriors go on and beat the Bulls in the playoffs the pain of it will be forgotten.”

Sullivan’s obituary in the Examiner stated that he was the inspiration for Neil Simon’s character “Oscar Madison” in the Odd Couple. in 1975 he was one year away from retirement from a 54-year career. In fact, his next paragraph in this column was to liken “Barry’s Boo-boo” to the fate of “Wrong-way Reigels,” who famously ran with a football toward the wrong end zone in the 1929 Rose Bowl, a game Sullivan covered. I am happy to report that Sullivan’s prediction in this case was 100% perfect. I remembered much about this series, but that fact had escaped my memory, and nobody, fan or media alike, whom I’ve spoken to about it has remembered it either.

I’ll bet Rick hasn’t forgotten, though. If you see him, please don’t tell him that I told you. We’ll let Prescott Sullivan’s prediction stand.