Almost.

The word often speaks to excellence, but it ultimately weighs down the heart and the soul of any competitor.

Spill your guts in a four-hour tennis match, gain match point, and almost win.

Play the heavy favorite into overtime in an NFL playoff game… and almost pull off the upset.

Take Michael Jordan to the brink of… well, the brink… and almost force a Game 7 in two separate instances.

Almost — it is the Utah Jazz’s greatest distinction in franchise history, which conveys so much of their greatness, and yet is a statement of the organization’s snake-bitten history.

*

The Utah Jazz were not the best Western Conference team in the 1990s. You either have to give that distinction to the Houston Rockets (as an organization over multiple seasons) or the 1996 Seattle Sonics (in terms of a single-season team pitted against the other single-season Western Conference champions from the decade).

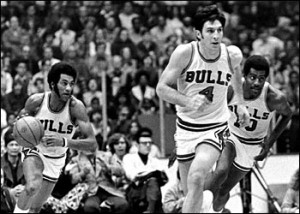

The late-1990s Jazz were cut from the cloth of their head coach, former Chicago Bull star Jerry Sloan.

A tireless worker as a player, Sloan achieved all that he did in the Association by scrapping for it. Some coaches — think of Billy Cunningham — were a lot more restrained on the bench in a suit and tie than they were as players. Sloan? Every last ounce of his competitive fire showed in the way he coached the Jazz. He was the same person, without need for modulation or readjustment.

In Game 7 of the 1996 Western Conference Finals, Sloan’s Jazz fell to the great Sonics in Seattle, and given the history of the Jazz, it would have been very easy to think that another late-May or early-June heartache was on its way in 1997. However, the Jazz learned from that agonizing experience and managed to bust into the NBA Finals for the first time. Karl Malone — The Mailman — delivered for this team on a consistent basis, but the biggest moments in franchise history were more often authored by John Stockton, never more so than on the night the Jazz played deep into the night, sweet and happy, in Salt Lake City.

The residents of the Beehive State partied for a good long while after they saw Stockton hit this shot in Houston, winning (Game 6 of) the 1997 West Finals against the Rockets:

Finally, the Jazz and Salt Lake City had earned their moment in the spotlight.

Much as the city of Phoenix hit the big time in professional sports in 1976 with the Suns’ first Finals appearance, and much as Portland registered on a national level with the world champion Trail Blazers in 1977, the NBA once again became the portal for a Western city to make its mark on the American sporting landscape.

The Jazz — with a bunch of junkyard dogs named Bryon (NOT BYRON!) Russell, Shandon Anderson, “Big Dog” Antoine Carr, and Greg Foster — supplemented their big three of Malone, Stockton, and Jeff Hornacek enough to conquer the Western Conference. This was not a blindingly talented team, but the consistency of The Mailman — combined with the basketball IQ and competitive chops of Stockton, plus the sweet stroke and tireless work ethic of Hornacek — formed enough of a foundation to let the role players defend and rebound with abandon. With the Rockets aging and also devolving into hero-ball with Chuck Barkley, and with the Sonics failing to sustain the magic they found in 1996, Utah created a two-year window in which it owned the rest of the West. The feat remains impresssive today, for a few specific reasons.

*

In the 1990s, only three West teams repeated as conference champions: the Rockets in their back-to-back world championship years; the 1990 and 1992 Trail Blazers, and the 1997 and 1998 Jazz. Only Houston and Utah went back-to-back in winning the West, so Sloan’s squad distinguished itself even more in that regard.

In one of the great what-ifs of NBA history, Jordan’s Chicago Bulls never got to play the Rockets — with Hakeem Olajuwon in the middle — in the NBA Finals. Of the West’s other two “double-Finals” teams from the 1990s, the Blazers and Jazz both pushed Chicago to a 2-2 series tie, but only Utah made the Bulls sweat in Game 5.

Chicago cruised past Portland in Game 5 of the 1992 Finals, dominating the first three and a half quarters and winning without incident, 119-106.

In order for the Bulls to take a 3-2 lead over the Jazz in the 1997 Finals… well… something truly extraordinary had to occur.

First, though, the series had to be tied 2-2 for Game 5 to take on the added dimensions it acquired in the fullness of time.

How did Utah square the 1997 Finals in Game 4?

With this magical display from Stockton, complete with a touchdown pass that was everything a Brigham Young University quarterback proved to be for that ascendant football program in the 1980s:

If Stockton was magical in Game 4, though, this fellow named Michael Jordan was the wizard of all wizards in Game 5. He cast a spell while not feeling remotely well. The greatest player in NBA history (this side of LeBron James) played his greatest game, and even then, the Jazz very nearly won:

The Jazz did push the Bulls harder in 1997 than any other Finals opponent had in previous years, but Jordan had the final say. The Jazz earned so much respect, but the word “almost” still lingered throughout a long offseason and an even longer regular season.

When the Jazz defended their West title with a sweep of the young Shaq-and-Kobe Lakers in the West finals, they got their shot at a rematch with the Bulls in Jordan’s last go-round with Phil Jackson and Scottie Pippen.

While the Bulls — in an eerie repeat of the 1993 Finals against the Phoenix Suns — did take a 3-1 series lead at home, this series did become more precarious for Chicago than the 1993 Finals. Pippen was going to be doubtful at worst, highly compromised at best, for Game 7 due to an injury suffered in Game 6. Chicago did not face such a problem in 1993. The Jazz were right there with a chance to finally take Jordan to a Game 7 in a Finals, something that hadn’t happened in M.J.’s previous five trips to the Finals.

Well, you know how the 1998 Finals ended:

The NBA is a superstar league, as everyone knows, and its greatest superstar (whose box-office power will always exceed LeBron, regardless of whether that’s right or wrong) got one last superstar-level call against Russell to plunge the dagger into the Jazz’s hopes of being the first team to at least make Jordan go seven in The Finals, let alone beat him for the world title.

The Jazz had in many ways done more than any other Jordan opponent on the sport’s biggest stage, but all they had to show for it was this lousy (Western Conference Champions) T-shirt… and the word “almost.”

*

If you were to compare the 1997 and ’98 Jazz to the early-1990s Trail Blazers, the edge in terms of pure talent would go to Portland. Terry Porter, Clyde Drexler, Jerome Kersey, Buck Williams, and Kevin Duckworth possessed more all-around physical prowess and holistic skill than the Jazz starting five of Stockton, Hornacek, Russell, Malone, and either Greg Ostertag (1997) or Adam Keefe (1998).

The Jazz made their team work, though, because Stockton and Malone formed such a lethal pair, a combination which enabled the Jazz to play either inside-out or outside-in with their two-man games and the many pick-and-roll variations which defined it. Portland didn’t have quite that same capacity with a lineup whose strengths were more located on the perimeter and the wings. Malone was an elite interior scorer with a polished mid-range jumper, and that set of skills trumped what Williams and Duckworth gave Portland.

The other reason the Jazz did a little more than Portland — and can therefore claim to be the second-best Western Conference organization in the 1990s NBA — is that Sloan wouldn’t let the team slack off. With all the grunt guys on this team — all the defenders who made those 1997 and 1998 Finals games low-scoring — there was no time for complacency. Utah scratched and clawed at the Western Conference door for many years, but the Sloan formula finally found fruition in 1997 and 1998. It was and is (and always will be) a feat forged primarily by the core of Stockton, The Mailman, and a key assist from Hornacek, but Sloan’s role in pushing this team to greater heights in the late 1990s cannot be overstated.

*

EPILOGUE

In stepping back a bit from this appreciation of the Jazz, the one particularly poignant part of their “almost-ness” is not just that Sloan, Stockton, and The Mailman never won an NBA title. It’s that Malone — clearly overshadowed by Stockton in the 1997 Finals — put together a better 1998 Finals series, only to falter when the moment became magnified. On a related note, Malone was at his very best when the Jazz were in their most vulnerable positions, but couldn’t then deliver when Utah was on the cusp of gaining an advantage in its two series against the Bulls.

Let’s take that last point first and then explain why Malone’s 1998 Finals were still marked by disappointment:

The Mailman was at his best when the hour was darkest for the Jazz in both 1997 and 1998. In 1997, Utah was down, 2-0, in the series. Malone answered with 37 points in Game 3 to pour life back into the team and its title hopes. In 1998, with the Jazz down 3-1 and having to play Game 5 in Chicago, Malone rose above what was a (typically) rugged and ugly game to score 39 points and carry the Finals back to Salt Lake City for Game 6. Without Malone, Utah wouldn’t have even had a chance to push the series seven games. Moreover, in Game 6 of the 1998 Finals, Malone sparkled again, throwing down 31 points and carrying his teammates for long stretches.

If he wasn’t quite up to par in 1997, Malone raised his game in 1998. He was everything this team could have asked him to be in the repeat Finals matchup — he answered the bell the way superstars do, and must.

This leads back to the first point, about excelling and yet still being laden down with the weight of “almost”:

For all the parcels The Mailman carried for the Jazz in the 1998 Finals, all anyone ever remembers from that series is the turnover committed in the final minute before Jordan’s last bucket as a champion and as a Chicago Bull in Game 6. History is cruel that way, but no one ever said the NBA was fair.

The Utah Jazz could tell you all about it, 17 years after the fact.